The re-launch of the Reading International program sees Chris Zhongtian Yuan, originally from China but living in the UK, display recent films including Wuhan Punk (2020) and Cloudy Song (2022) in the aptly chosen 571 Oxford Road Gallery, situated on the unusual but lively road off the Berkshire town’s city centre. The rustic former army barrack, surrounded by imposing Ministry of Defence signs and international food stores, juxtaposes Beijing’s chic Macalline Art Center, which is showcasing the second half of the artist’s project simultaneously.

Yuan’s film ‘Wuhan Punk’, accompanied to its left by an arrangement of screws forming an anarchist symbol, completes the first room. The work is composed of a mixture of urban footage and digitally rendered landscapes, accompanied by a paced but melancholic combination of chinese punk music, radio reports, and narration. The muggy, overimposing urban landscape of Wuhan, scattered with mysterious and ambiguous spaces that dissent from the rigidity of the usual concrete structures, is haunted by a figure from the city’s punk music scene in the 90s. Beneath the surface of the city, a rebellious underground scene appears to be alive; or at least that is what the narrator hopes, believes, or dreams.

A glimpse away in a second room, the artist repurposes some of the building’s original architectural features such as a small kitchen and an old door, displaying objects featured in their second film, ‘Cloudy Song’. In one corner, a television showing raw footage from an underground Wuhan punk rave faces a single lamp on the opposite side of the space, illuminating two photographs from the artist’s childhood pinned to the wall. Next to the lamp, an architectural model of their childhood home completes the liminal and nostalgic scene.

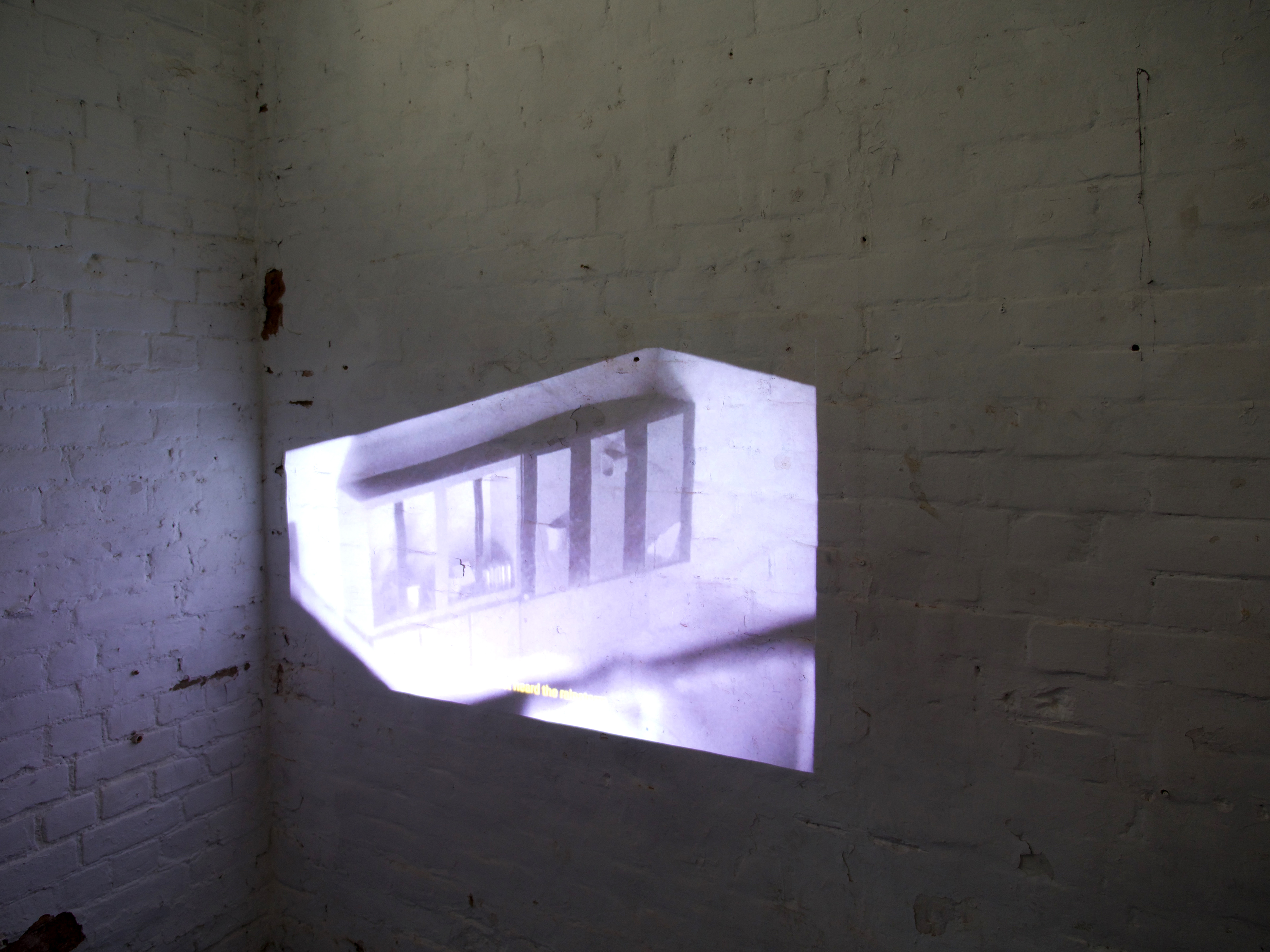

The film ‘Cloudy Song’, shot on 16mm black-and-white film, features a mysterious ghostly figure suffering from amnesia, wandering through a barren landscape of curtains and concrete. As the film progresses, an AI presents the figure with a film of a punk rave, excerpts of Chinese popular music, and a model of a childhood home, all recognisable from the aforementioned installation, in an attempt to help it regain its memory. In the final moments of the film, the artist joins the figure on stage, set to increasingly loud atmospheric music. Following the screening, viewers are invited to step into an aerie yellow-tinted hallway, accompanied by a mixture of urban sounds and voices.

For those aware of the British punk scene, Chris Zhongtian Yuan’s work provides an exploration of the ways in which its themes, motifs and values can haunt different areas of space and time. Despite initially appearing to have a highly referential nature, the Wuhan punk scene, part real and part artistic fiction, ends more authentically representing the values of rebellion and dissent than what remains of the ‘mainstream’ British punk scene, perhaps already oxymoronic by name: think republican-turned-monarchist John Lydon.

However, Wuhan punk is more than a historical phenomenon that is simply intriguing because of how it demonstrates the permeability and recurrence of culture. For the artist, the underground scene also forms part of a subjective, personal memory of home, which can be distorted, instrumentalised, and interpreted in various ways. Accordingly, the exhibition asks the question of whether memories can have meaningful things to say about places in time, or whether they say more about those who possess them.

We learn that Wuhan punk, as an abstract concept, is an invisible ether of disobedience and nonconformity that may still haunt Wuhan and wider Chinese society, at least per the memories of the artist. Is this just a matter of perspective, maybe something you have to squint to see, or something that is so wide in the open that you don’t even notice it? I am reminded of a memorable scene in Hsu Che-Yu’s film Re-rupture (2017), selected by Yuan for an accompanying screening, depicting a punk musician playing a guitar while floating above a Taiwanese city strapped to a balloon. The result is a wonderful expression of optimism, and an intriguing examination of civil society and the expression of implicit socio-political norms in communist China and elsewhere.

The choice to host such an important exhibition in Reading, seemingly doomed to forever lie in London’s shadow, also raises questions regarding the town’s cultural development, some of which were previously discussed during the pre-pandemic iterations of the Reading International program. The British contemporary art scene, bar some public institutions, resides almost exclusively in the capital. Increasing access to more people appears reasonable, if only through publicly funded projects such as this. But if the locals won’t even show up, should anyone bother?